Hi! Aaaaand, we’re back. I shut down this blog first when I began writing more regularly for Business Insider, and then when I worked full time on the launch of my startup, Card.biz, backed by Kima Ventures. Now that we’ve launched our beta, I’m starting PEG on Tech up again.

When I was in New York last week, I had a drink with a prominent entrepreneur who asked me why so few European startups manage to get above a billion dollars in value. In fact, the list is very short: Vente Privée, Betfair, Skype (if you can still consider it a European startup)…

The question caught me off guard, so I gave a bad, bumbling answer, but it got me to thinking. Usually us European entrepreneurs think about the question from the other angle: why is it so hard (?) to start a business here? We don’t usually think about the other side: why is it so hard for businesses to grow very large?

But it is, also, a fascinating question, first of all because some of us in Europe do want to build billion dollar businesses (even billion euro businesses) one day, and second of all, because it is connected to the first one: surely, if there was a “European Google”, the whole startup ecosystem would be healthier.

After thinking about this for a week, here’s what I think matters the most. Most of these aren’t new, but they helped clarify my thinking. I hope it does the same for you. I’ve ranked them from most to least politically incorrect. 😉

- Fragmented market. This is the most obvious one. Particularly in the consumer web, getting to scale is much harder in Europe than in the US because people have different languages, but often also different cultures. Getting to Germany doesn’t just mean translating the site, although that can be a pain in the ass, but also scaling support, recruiting salespeople, maybe opening an office, etc. — and fending off the inevitable local competitors. If you want to sell to ad agencies, you often have to pitch both the European headquarters in Paris or London and to the local offices in various countries; if you want to recruit that rockstar Swedish developer, well, he almost certainly speaks good English as a second language, but is he going to want to move to Paris to interact only in English with other people who also speak English as a second language (and in the case of a Paris-based startup, poorly (sorry guys, but it’s the truth))? And so on down the line. Bottomline, while it takes all the effort in the world for a startup to go Europe-wide, by that time your US competitor has grown much faster, is global, and can pummel you. This is what happened to both web 1.0 portals and social networks, who are just no match for Facebook’s size and attendant network effects.

- Less exits. This is sort of a chicken and egg thing, but it’s the $10M and $100M exits that set the stage for the billion dollar exits. Because they give founders early liquidity so they can embark on more ambitious projects or fund more young upstarts, because they give founders and employees experience, because they make it a less daunting proposition to start your own company, because they give VCs “long tail” returns that help them raise more capital and pump more of it into startups. Why less exits? As I said before, there is no “European Google” to make acqui-hires at $10M a pop seemingly every other day with their sky-high stock (incidentally, it’s a shame that the EU startups that are big are not going public). What’s more, European media and software companies are really, well, afraid of the web. Part of it is legitimate — they got badly burned several times — but part of it is just neanderthalism. Look at the social gaming industry. Playfish (the one European big player) got acquired by… Electronic Arts, a Silicon Valley company! Even though the world’s biggest gaming conglomerate, Activision, is owned by Vivendi, a French company! And now Playdom just got bought by Disney. Both of these are really great deals. These companies are, like all in their sectors, presumably very profitable. These big companies are getting access to a market that is hugely growing, both in profits and “mindshare”, and the synergies from using their awesome brands for new social games are obvious. Euro media companies just completely dropped the ball, here.

- Europeans have less money. This is politically incorrect, but it’s true. We Europeans like to think of ourselves as basically equal to America in terms of development, importance, etc. (and morally superior, of course) but it’s just not the case. GDP per capita in the EU is $33,052 (source) versus $47,988 (source) in the US, and that doesn’t even factor in their much lower taxes. This has many consequences. People are more willing to spend money on new, risky (more on which below) things. Have more disposable income to buy books online. And, of course, are more valuable to advertisers, which in the consumer web world of dirt-cheap CPMs can make a huge difference — between life and death, or between mere viability and scale.

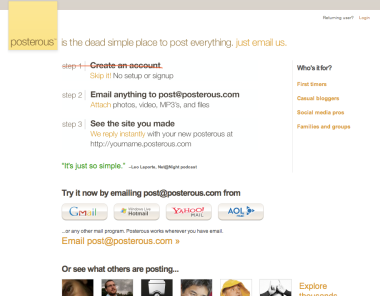

- Europeans are cowards. This is a harsh way to put it, but bear with me. When discussing why Europe lags the US in entrepreneurship, people often discuss “culture,” and from the entrepreneur’s perspective: less encouragement of risk-taking, a taboo on money-making, on success, on empire-building. All of this is correct. But if you want risk-taking entrepreneurs, you need risk-taking consumers. This is one of the ideas of economist Amar Bhidé’s book The Venturesome Economy. He points out that American consumers are more willing to just try things. Part of it is more disposable after-tax income, but part of it, I suspect, is just culture. Bhidé takes the example of the iPod. Today we’ve forgotten that for several years after it was introduced, the iPod was not the smash it we now know it to be, but simply a middling product — not a dud, exactly, but not doing particularly well. It wasn’t a great product. And during that time, Apple refined it and refined it until it blew up and Changed Music Forever™. Even assuming a European company had had the balls and the talent to come out with something like the first generation iPod, they would’ve killed it after a year because nobody would’ve bought it. Forget the risk-taking entrepreneurs — you’ll find crazy people (a category of which I proudly count myself) everywhere –, if you want an economy of innovation, you need risk-taking customers. You need at least enough, a small critical mass, of people who will try things, even if they’re not perfect, either because they’re new, or simply just for the hell of it. The most common question I get at a cocktail party in France when I describe some new service like Facebook or Twitter or Foursquare is “Why would I use it?”, at which point I have to bite my tongue not to say “Why the fuck not! It’s free! Try it! You might not like it but why do you need a reason just to TRY it!” By default, Europeans distrust “what’s new” while it appeals to Americans. This is a gross overgeneralization of course but I think in aggregate it holds true. I think this lack of a “venturesome European consumer” is the most non-obvious, important reason why Europe has a third-rate (sorry) innovation economy. The problem is that it also sounds like the hardest to solve.

What do you guys think? Why is Europe behind? Did I get some of these wrong? Are there some other reasons you can think of?

Photo: “Barcelona” by Flickr user MorBCN (CC)